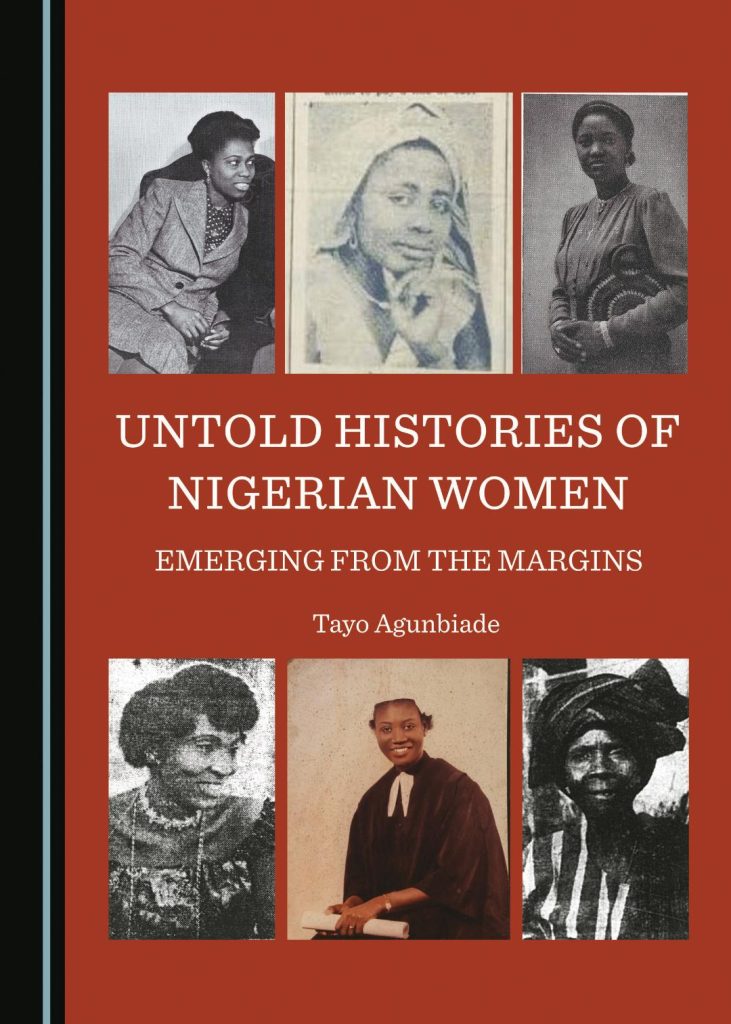

Untold Histories of Nigerian Women Emerging from the Margins

Untold Histories of Nigerian Women: Emerging from the Margins by Tayo Agunbiade is a 20-chapter book which redefines the scope and text of Nigeria’s 20th century historical narratives. It is based on research conducted at five branches of the national archives across Nigeria which unearthed British colonial-era administrative documents such as correspondence and memos between bureaucrats; annual colonial reports, minutes of council meetings, petitions, as well as primary source material from Nigerian historical newspapers, magazines and journals.

This book retrieves women from historical invisibility to challenge Nigeria’s male-centric historiography and enriches the text of global historical narratives. It records hidden and over-looked archival information about the voices, experiences and accomplishments of women across the country from 1922 to 2022, to reveal their contributions in the shaping of society.

Forgotten and poorly-known episodes of deputations, street marches and resistance led by colonised women against unpalatable ordinances receives extensive attention in this book. Protests against colonial and political domination; unwelcome town council policy on markets, land seizures and women’s taxation, as well as more contemporary instances of dissatisfaction with corporate governance in the private sector and protests against mass abductions of school girls are chronicled for historical memory.

Episodes of push-backs from women through mass protests, sit-ins, court actions, petitions, public statements and syndicated letters etc against colonial and indigenous male domination are also documented in several chapters to serve as lessons for future generations.

The petition power of Alimotu Pelewura in 1940, as well as the unsung voices of other working-class Lagos market women leaders like Modinatu Alaga, Rabiatu Iyalode, Jariogbe Oniwaka, Osenatu Dosunmu and Bintu Balogun who confronted colonial administrators and local municipal council bureaucracy alike, come out from archival shadows into the limelight. Similarly, the audacity of a group of middle-class women of Warri Division in Southern Nigeria who in 1943 boldly submitted a memorandum making social demands from the colonial administrators formed the basis of a chapter. Through this book, the names and agency of pioneering women councillors in the Western and Eastern provinces have taken their place in history. The public writings of women’s rights advocates such as Elizabeth Adekogbe, Theresa Ogunbiyi, Ladi Shehu, Margaret Young and Victoria Omene, as well as those of women commentators who sought social and political reforms and female representation in parliament are re-produced to historicise their voices and views.

This book narrates the historical context behind early parliamentary speeches of the 1950s historical figures of Remi I. Aiyedun, Margaret Ekpo, Janet Mokelu and Ekpo Young, as well as those of First Republic Senators Wuraola Esan and Bernice Kerry. They are now all given their rightful place in Nigeria’s history. The political rhetoric of intrepid women campaigners such as Adanma Okpara, Ladi Shehu, Adunni Oluwole, Gambo Sawaba, Faderera Akintola and Hannah Awolowo now deservedly has a space in Nigeria’s historiography.

From 1933 onwards, women such as Stella Jane Thomas, Adebisi Adedoyin-Adebiyi and Olabisi Alakija who broke into an exclusive male territory are no longer anonymous as archival findings showcase their courage, and ventures into nationalist politics and activism.

Official documents reveal the patriarchal ideology of British colonial administrators towards girls’ education as being solely towards the private sphere of “marriage and home management,” as well as their frowning on recruitment and employment of colonised women into the public sphere of the civil service. Similarly, insights into the thoughts of women education superintendents such as Sylvia Leith-Ross, C. L. H. Geary and Gladys Plummer as they implemented a domestic science ideology across the northern and southern provinces, are included as part of the historical journey of girls’ education in colonial Nigeria.

A recurring theme that emerged from the piles of archival material and which still exists today is male domination of Nigeria’s political and socio-economic structures. To analyse the depth of this culture of male hegemony, this book traces the historical journey of the patriarchal and hierarchical patterns of electoral restrictions, political party structures, constitutional development, deliberative institutions, the national honours list and the collective impact on women’s representation in society. This book also re-produces an array of male-oriented articles, editorials and letters published on the pages of the nationalist newspapers, which provide a window about men’s perspectives on the place of women in the socio-political order.

The historical and contemporary evidence documented in this book demonstrates that a remark made by the earliest woman politician, Oyinkan Abayomi, to the local press in May 1944 that “the interests of women are sorely neglected” is still relatable in Nigeria.

BOOK REVIEWS

" Tayo Agunbiade has used extraordinary reserves of tenacity and determination to bring to light the neglected stories of the Nigerian Women who have shaped their country’s history. But her book is also full of empathy and love for these Women, who battled discrimination in the colonial period and bravely continue to do so today. She has done them proud with this pioneering study, and thereby filled a glaring hole in Nigerian historiography. "

" An encyclopedic volume and a truly remarkable work by Tayo Agunbiade, who has managed to write a book which reinstalls Nigeria’s Women into their country’s history over the past century, from 1922-2022. Expertly researched, concisely written and lavishly illustrated, it will surely become the standard work on the subject. Untold Histories of Nigerian Women is exactly what it claims to be, a fascinating record of the lives and experiences of those hitherto largely marginalised from history. Essential reading.

"

" Tayo Agunbiade's study is a very welcome and much-needed contribution to the histories of Nigerian women - that's histories, plural, as part of her work's value is in showing that there is no one typical figure, as she finds people who took a huge variety of political positions and life pathways. Nigeria's historiography, like its politics, has been dominated by a patriarchal take on the country's trajectory, so Agunbiade's book will be a welcome corrective which is likely to be in long use as a source-book on a whole range of little-known lives and works. She is a scholar by natural vocation whose diligence and curiosity about her subjects shines out from the pages. "